Our food system is facing an unprecedented crisis. The lives of hundreds of millions or even billions is in jeopardy. We are facing four dilemmas simultaneously, all related to our dependence on fossil fuels that are finite in nature.

Our food system is facing an unprecedented crisis. The lives of hundreds of millions or even billions is in jeopardy. We are facing four dilemmas simultaneously, all related to our dependence on fossil fuels that are finite in nature.

The first dilemma is about the direct impact of higher oil prices on agriculture: more expensive diesel for tractors, more expensive pesticides and herbicides and more expensive transportation costs for all farm inputs and outputs.

The second dilemma is an indirect result of higher oil prices – an increased demand for biofuels that in turn results in more farmland going to crops for biofuel production rather than food production, driving up the price of food.

The third dilemma relates to the effect of climate change and extreme weather conditions caused by greenhouse gases released when fossil fules are burned.

Today climate change has become a critical issue.

The depletion of fossil fuels exacerbates the issue and if we do not succeed in solving both problems, we could face disaster on two fronts.

A final issue looming over us is the degradation or loss of basic natural resources – primarily arable land and fresh water – resulting from high production volumes using unsustainable methods made possible by cheap energy.

Fresh water is another natural resource that will become scarce.

It would be wrong to suggest that the rise of fossil fuels has had no positive effects. In the late 19th century, about a quarter of American and British farmland was devoted to growing grains for horses, the main draught animals. The switch to mechanical horse power freed up this land for the production of additional food for human consumption.

In a century the application of fossil fuels in agriculture has grown beyond all proportions. This inbalance can be expressed in calories. The production of one calorie of food energy costs 10 calories of fossil fuel.

Agriculture is mass production

We have now reached a phase in which peak fossil fuel production is approaching, which will force us to adapt to falling energy production and rising prices at the same time. This is due to the scarcity of fossil fuels and the lack of effort put into developing alternative sources of energy. Peak fossil fuel production does not occur in all countries simultaneously. It happened 30 years ago in the US; North Sea oil has also passed its peak; yet other places have not yet reached their peak. According to some, aggregate world production still has not yet reached a peak, although it will not be long until it is reached. The last peak in oil production was attained in May of 2008, almost three years ago. The revitalised coal mining industry is supposed to fill the gap.

In the meantime, food prices are rising by leaps and bounds. Grain supplies have been run down to 57 days, the lowest level in 25 years. High food prices are good for farmers as long as the extra income is not entirely absorbed by higher input prices for fuel, fertilizer and pesticides. Farmers with low inputs suddenly be at an advantage.

However you look at it, the urban poor will suffer under increasing food prices.

Impact of biofuels

Farmers face a dilemma with the rise of biofuel crops: either continue producing food crops or switch because growing fuel crops pays better. A fifth of corn production currently goes into the production of ethanol. This is expected to rise to 25% in the near future. The result of this shift is a skyrocketing price for corn that impacts both human and livestock consumption. Heinberg does not mention that the use of the crop is not determined by the farmer but by the buyer. The dilemma faced by the farmer only concerns the crops that can by processed into biofuel. This is still not the case for the current corn, soy, rapeseed, and sugarbeet varieties. As soon as varieties of these crops appear specially developed for energy extraction, the farmer will face a dilemma

Phosphate

The availability of phosphate mined for fertilizer is decreasing. Peak world phosphate production occurred in 1989. The richest mines are depleted and we are now extracting this mineral from lower grade mines at much higher prices.

Organic farming

Mankind will be forced by circumstance to return to an agriculture less reliant on fossil fuels. Organic farming can be a solution, a solution that will also result in greater employment in agriculture. Much knowledge will need to be acquired about the nature of the local land, micro-organisms, climate, and the interaction between plants, animals and people.

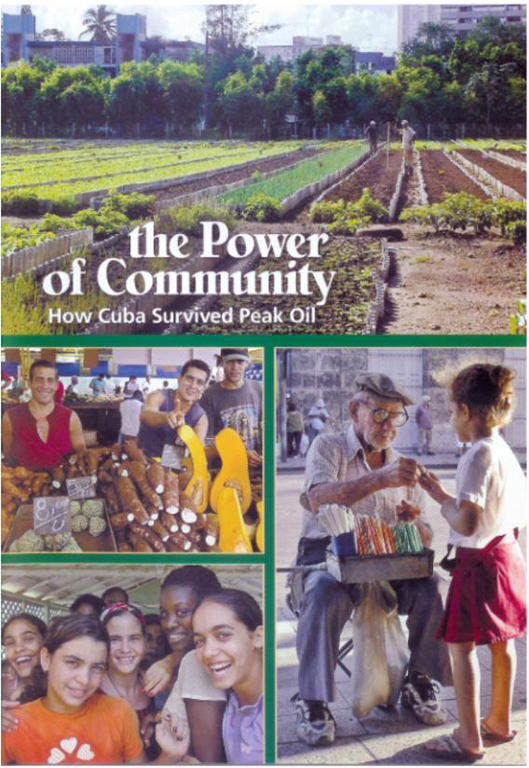

Cuba as harbinger

The farmers and citizens of Cuba found out what a shortage of fossil fuel means first hand at the end of the eighties. The average weight of the population fell considerably and malnourishment was common. State farms that were performing poorly were disbanded and land was redistributed. The ox replaced the tractor. Organic farming, using a combination of animal manure, compost and natural approaches to fighting pests and plagues grew. Cubans became vegetarians out of necessity. Farm labourers’ wages rose above those of civil servants and office workers. Garden allotments and even rooftop gardens emerged. This is how a disastrous famine was avoided.

How was Cuba able to switch so rapidly to an oil-free economy?

Power of Community: Hoe Cuba survived Peakoil

This issue also occupies the various Transition Towns, which exist to exchange knowledge, increase awareness among the general public and take action – by finding places to grow food or networking with local farmers.

The turning point is imminent

The first steps are being taken in the US. Recently Oakland, California decided to pass a bill requiring 40% of all vegetables consumed in the city to be grown within an 80 kilometer radius of the city centre.

Heinberg expects that there will be renewed appreciation for draught animals. Oxen will be favoured over horses because they will eat straw and stubble; a horse likes oats and therefore competes directly with humans for land. As tractors are replaced by draught animals the need for economies of scale in agriculture will subside and the landscape will change accordingly.

Heinberg suggests that humans will all be eating organic food out of necessity in a hundred years because fossil fuels will no longer be available.

Richard Heinberg held a speech on this topic in Central Hall, Westminster, London, on 22 November 2007.

His speech can be found in its entirety on his website – What will we eat as the oil runs out?

Source (Dutch): Workgroup for Just and Responsible Agriculture Wervel vzw

Ilse Hoenderdos, Eindhoven–